Football in the nineteen-eighties was on its knees. Its stadia was crumbling and largely unfit for purpose. The reputation of its supporters was at an all-time low.

With hooliganism so prevalent it is no exaggeration to claim that within the media and mainstream, fans were viewed as an undesirable subset of society. Separate from. Other.

In 1985, the Sunday Times ran an editorial that damned football as ‘a slum sport played in slum stadiums increasingly watched by slum people’.

That same year, thousands of Bradford City supporters attended the final home game of their season and having already secured promotion the mood was celebratory.

Just prior to half-time a lit cigarette rolled through a small gap in the floor of the main stand and landed on a mound of debris and discarded paper.

As flames took hold and soon after reached the highly flammable bituminous roof, engulfing the entire stand in fire, fans desperately tried to escape via the rear. They found every exit locked with no stewards around to open them.

Fifty-six people lost their lives that afternoon.

A fortnight later came Heysel, a horrible maelstrom of all of football’s ills coming together to bring further tragedy. It was hooliganism that led to Juventus fans retreating en masse across the terraces.

It was a decrepit, ramshackle stadium that resulted in 39 lives being lost, as a wall easily collapsed.

On the same day as the Bradford stadium fire, a 14-year-old boy died as violence broke out at Birmingham’s St Andrews while the appalling scenes at Kenilworth Road earlier that spring, that had Millwall’s Bushwacker firm running riot, shocked the nation.

To address a clear and disturbing nadir of a wonderful sport played in slum stadiums, watched by perfectly decent people, but with a fringe element of idiots who ruined it for everyone, Margaret Thatcher formed what she referred to as a ‘war cabinet’.

What’s the betting that some truly obscene suggestions were put forward in those meetings?

As a case in point, Chelsea chairman Ken Bates advocated the introduction of electrified fences. He said, “People may howl about it being dangerous, but it’s been used in farming for a long time.”

Seven years before the Premier League was formed and ten years before all-seater stadiums became compulsory, this was football in the UK. This was 1985.

The following March a publication appeared, sold outside various grounds or found in select bookshops.

Called When Saturday Comes it was a DIY magazine that featured blurry typewriter-font and crudely drawn cartoons but none of that mattered a jot. What mattered was that each article was written from a fan’s perspective.

Mixing humorous anecdotes from awaydays and serious campaigning pieces taking aim at a government that vilified fans as second class citizens, it was a revelation. For the first time, football supporters had a voice.

Now a well-established and highly respected football publication in its own right, WSC wasn’t a voice in the wilderness for long

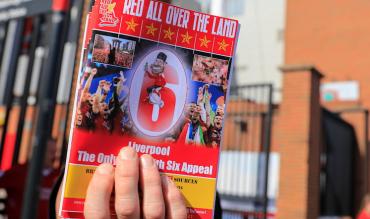

That’s because in its wake appeared hundreds of similar publications, typically focusing on one club and almost always irreverent and insightful in equal measure.

Inspired by the punk ethic of a decade earlier – it was not unknown for issues to be put together using works photocopiers when the boss wasn’t looking - and born from necessity, a fanzine explosion brought light and shade to football’s darkest days.

Arsenal had The Gooner and a superb read it was too. Their Premier League odds may presently have them favourites to win the title but back then, in the early days of George Graham, success continued to allude them. Consequently the writing is biting and beautifully morose.

Leeds had The Square Ball. Manchester City had King of the Kippax. Edited by a 16-year-old Andy Mitten, Manchester United had United We Stand.

Endearingly, the lower down the divisions you went, the sillier the titles seemed to be. Famously, Gillingham’s fanzine paid homage to a well-known fan of the Gills by taking its cue from a Half Man Half Biscuit lyric. Brian Moore’s Head Looks Uncannily Like London Planetarium was regularly voted in as one of the best ‘zines around.

Increasingly on matchdays, supporters got into the habit of buying a fanzine, giggling at the jokes at half time, or nodding in agreement to criticism of their club chairman. Increasingly too, sales of football programmes dwindled, as they began to look staid and too establishment in comparison.

It was no longer just a revelation. It was a revolution.

And in all truth it was a much needed one. Because not only were these lovingly created publications at the vanguard of fan activism, but they also demonstrated something that of course was blindingly obvious, and shouldn’t need illuminating, but back then did.

That fans were intelligent, and silly, and passionate, and above all else, decent. Fanzines gave supporters a voice, and in such troubled times, my goodness, they were worth listening to.

*Credit for all of the photos in this article belongs to Alamy*